Simon Rogers has published a fantastic interactive graphic for the Guardian Datastore that maps teenage pregnancy rates in England and Wales from 1998 to 2010.

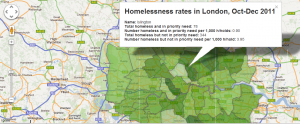

The visualisation shows the conception rate of under-eighteen year olds, per 1000 women, in different counties across England and Wales. The interactive map is an ideal way to present the information, as the visualisation contains a large amount of data in a comprehensible way. From the graphic we can derive that the number of teenage pregnancies has declined in the last decade, although this varies by area.

In order to focus on a specific county the user can scroll the mouse over the map and click on a different area, labelled by county at the side of the map. Once you click on a county the line graph changes to show the counties’ change in number of teenage pregnancies by year and how this compares to the England and Wales average. This allows the user to have more detailed and specific information simply by clicking on the infographic. Thus the graphic allows users to see the more personalised, local data.

By using this tool the user can focus on various localised data, and see how they compare with each other. For example, in Wales it is apparent that poorer counties, such as Merthyr Tydfil and the South Wales Valleys, are significantly over the national average regarding the number of teenage pregnancies. In contrast, geographically close but wealthier counties like Monmouthshire and Powys are below the national average. In most cases this has not altered over the decade.

The map thus proves that in certain circumstances seeing only the larger data can give a limited understanding, as it shows a national decline in the number of teenage pregnancies but does not tell us that many individual counties have not changed significantly. In this way a graphic of this kind presents to users the ‘big picture’, in a clearer way than text alone.

The graphic also allows users to ignore information that is not of interest to them and to focus on geographical locations that are. This gives users a certain amount of control over the visualisation, as information is not decided for the user, as would be the case with textual narrative.

The interactive element of the visualisation allows users to find the story or information for themselves with no difficulty. This is more satisfying than simply being told information. At a time when the general public’s trust in journalism is low, visualisations such as this demonstrate that the journalist has not played around and sifted information but presented all of it to the user and allowed them to draw their own conclusions. In this way the user can get a more detailed, accurate and neutral understanding of the issue presented. It also breaks down the barrier between journalist and user and implies trust in the user to interpret and organise the data in an intelligent way.

The graph also uses visual symbols to organise the large amount of data. The map of England and Wales is easily recognisable, as is many of the counties. The counties that are under the national average are a light shade of blue and this gets darker as the percentage increases. The use of blue and purple makes the map visually attractive and the differences in shade easily identifiable. It is apparent that darker areas cluster together and that generally the North of England is darker than the South. In this way the user can obtain information from the visualisation by looking at it alone. The darker shade of purple stands out amongst the generally lighter shades and thus the graphic signals to the reader some of the most dramatic information. Thus, although the user is given control and the freedom to explore the data and draw their own conclusions, visual signals guide them to the most extreme data.

The orange circle that is drawn around a county when it is selected contrasts with the blue, making it clear. It also correlates with the colour of the line graph, making the visualisation easily readable.

By pressing ‘play’ the user can focus on one county and see how it breaks down by each year, as well as how the colours across the UK has changed by year, thus presenting more information.

The visualisation thus works as it presents a large amount of data comprehensibly. It allows the user to interpret and organise the data, but gives them visual signals to guide them. It also gives information for the whole country, as well as localised data, thus presenting the ‘big picture’. It is clear and easy to read and breaks down the barrier between journalist and user. It is therefore an excellent way to present the data.