KRIK has developed a system of defence in situations when they are publicly attacked or when there is a smear campaign against them. “Threats have never stopped us,” Jelena Vasić said.

“We immediately write to all our donors, partners, national and international journalists’ associations, and public figures to tell them what is happening and ask them to give us official statements. Then we publish all of those statements, one by one on our website, so our readers can see that we have the support of professionals and of the community.”

KRIK also frequently ask their readers on social media for financial support, using this kind of incidents to expand their crowdfunding community and show that people of Serbia are on their side. This is not without reminding us of ProPublica’s “We’re not shutting up” campaign last year.

For additional security, they also have special procedures: journalists working on a story can only talk to their editor about it, KRIK staff also use Signal for telephone communications and encrypted emails.

Tiago Mali of ABRAJI pointed out that journalists facing threat shouldn’t do so on their own.

“It’s important that we unite to defend ourselves against them,” he said. “In Abraji, we monitor these threats and try to investigate aggressions against journalists. The spirit is: if you mess with one, you mess with all.”

The Brazilian organisation also has a project in place called Tim Lopes (named after a journalist that was killed in 2002) where journalists from all over Brazil investigate the deaths of other journalists.

NPR have a system in place to handle threats depending on the level. “We of course get a lot of social media threats that we have to choose whether to engage or not,” Amita Kelly said. “And some of our reporters felt threatened at campaign rallies, etc. But we are very lucky that it is not a persistent issue.”

How do you get hold of the data that your government or powerful individuals want to keep hidden?

For ABRAJI it all started with regularly scraping the judiciary system for lawsuits. “The problem is that there is no flag or anything structured in a lawsuit that tells you it is about censorship or content removal,” Tiago Mali said.

“So we have tried and improved different queries that get us closer to the lawsuits we are looking for. As we collect thousands of these lawsuits, we read every single one of them and sort and classify the ones related to the project. It’s a time-consuming process we automatised step by step.”

The team at ABRAJI now wants to work with machine learning for sorting and classifying the lawsuits. “We want to build an algorithm that makes everything automatically and we would use our time only to review these work” Mali said. “This would be a tremendous upgrade in efficiency but we still lack the funds to build this structure.”

For their database of assets of Serbian politicians, KRIK has used company, criminal, court, and financial records, but also land registry records, sales contracts, loan and mortgages contracts from Serbia and other countries such as Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Italy, Czech Republic (and even offshore zone — Delaware, UAE, and Cyprus).

“We have used FOI requests very often in this project,” Jelena Vasić said. “Major difficulties came from state institutions which stopped replying to our FOI requests, but at the same time they were revealing all details from those requests to politicians and pro-government media, which then used it in smear campaigns against KRIK.”

“In situations like this one, we talk to the Commissioner for Information of Public Importance and also write on our website and social media about the institutions that are not replying to our FOI requests. Despite all the efforts of the authorities to disable us from obtaining important information, we have managed to get to the majority of documents we needed.”

There is good impact, and there is bad impact

When investigating wrongdoing, trying to bring forward what is kept hidden or denouncing corruption, news teams aim for positive impact.

“Since the very beginning, we wanted to provide data so there could be more journalistic stories on how the politicians and judges are harming freedom of expression in Brazil,” Tiago Mali said.

“We managed to achieve this goal.”

Because Ctrl+X provided insightful data, freedom of expression, a subject normally ignored by Brazilian media, managed to made the news. At the end of the 2016 electoral campaign, more than 200 articles about politicians trying to hide information had been published in Brazilian media using the project’s data. All major Brazilian newspapers, relevant radios and a TV show ran stories on freedom of expression with their information.

Yet sometimes, an investigative project end up changing the law, and not necessarily for the better, as it was the case in Serbia:

“Because of our investigation, the Serbian Land Registry has changed the way of replying to FOI requests” Jelena Vasić said. “They have decided that every response from their office should get approval from the headquarters in Belgrade, which was not the case before.”

As for NPR, they’ve noticed a real hunger for fact checks and stories that seek the truth on government leaders. “Our debate fact check was the story with the highest traffic ever on npr.org with something like 20+ million views and people stayed on the story something like 20 minutes, which mean they actually read it,” Amita Kelly said.

What could be done to make the job of holding the powerful accountable easier for journalists?

Approve and enforce Freedom of Information Laws, that’s what Tiago Mali argues. “Here in Brazil, a big shift happened after the approval of our FOIA. When you don’t need to rely on the willingness of the powerful to give you information (because a law says so), everything becomes much easier.”

“I think it would be very useful if international institutions could react every time a reporter is exposed to public attacks, because here in Serbia our government is afraid of international pressure” Jelena Vasić added.

For Amita Kelly, it is definitely about pushing for more transparency all around, including laws such as the Freedom of Information Act they have in the U.S. where journalists can request government information. She also thinks news organisations should invest “in allowing reporters to get to know a beat”. Covering an area for a long time helps to develop invaluable sources and expertise.

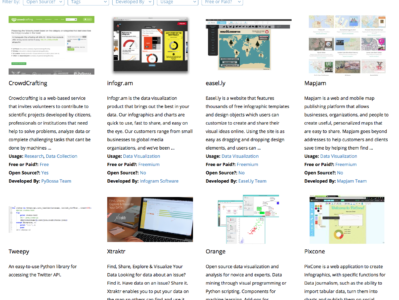

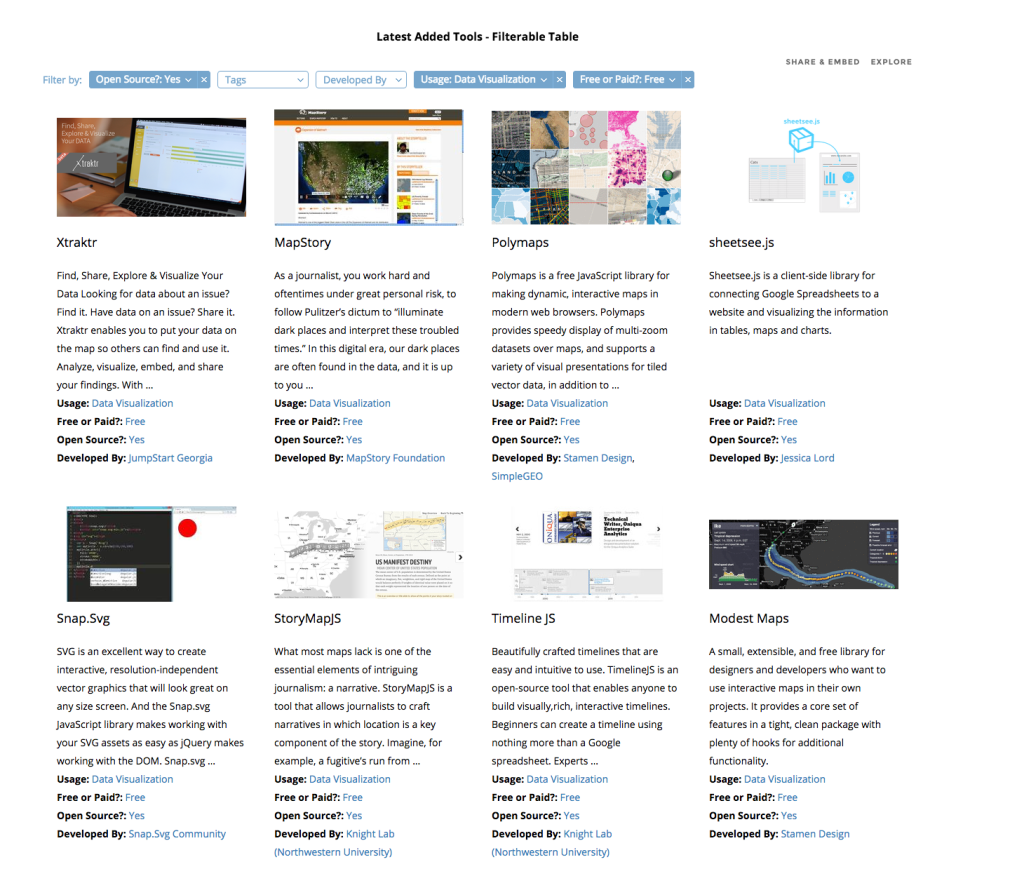

Bonus: tools and resources used in investigative projects

During our Slack discussion, Tiago Mali of ABRAJI revealed they used Parsehub for the CTRL+X project. It is a tool that easily extracts data from any website.

“We have worked with a lot of high-end tools here, programming, etc. But, still, I think there is no faster way to organise the information you work hard to collect than a spreadsheet. Sometimes the spreadsheet has to be a bigger database, a SQL or something you need R to deal with. But still, being able to make queries and organise your thoughts is really important to the investigation.”

Jelena Vasić loves to use companies search website poslovna.rs (similar to Open Corporates) and also Facebook Graph.

“We used different online sources, and were searching through different databases: Orbis and Lexis databases containing millions of entries of companies worldwide that also contain information on shareholders, directors and subsidiaries of companies.

Vasić also pointed at different local business registries online in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Czech Republic and local land registries in Serbia, Montenegro, Croatia.

“Google Docs is simple but has been amazing for collaboration,” Amita Kelly added. “At one point we had up to 50 people across the network in one document commenting on a live transcript.

Michaela Gruber is a journalism and media management student, based in Vienna, Austria. During her studies she spent a semester abroad in France, where she started working for HEI-DA.

Michaela Gruber is a journalism and media management student, based in Vienna, Austria. During her studies she spent a semester abroad in France, where she started working for HEI-DA.