This article was originally published on the Data Journalism Awards Medium Publication managed by the Global Editors Network. You can find the original version right here.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Peter Aldhous of BuzzFeed News and Simon Rogers of the Google News Initiative discuss the power of machine learning in journalism, and tell us more about the groundbreaking work they’ve done in the field, dispensing some tips along the way.

Machine learning is a subset of AI and one of the biggest technology revolutions hitting the news industry right now. Many journalists are getting excited about it because of the amount of work they could get done using machine learning algorithms (to scrape, analyse or track data for example). They enable them to do tasks they couldn’t before, but it also raises a lot of questions about ethics and the ‘reliance on robots’.

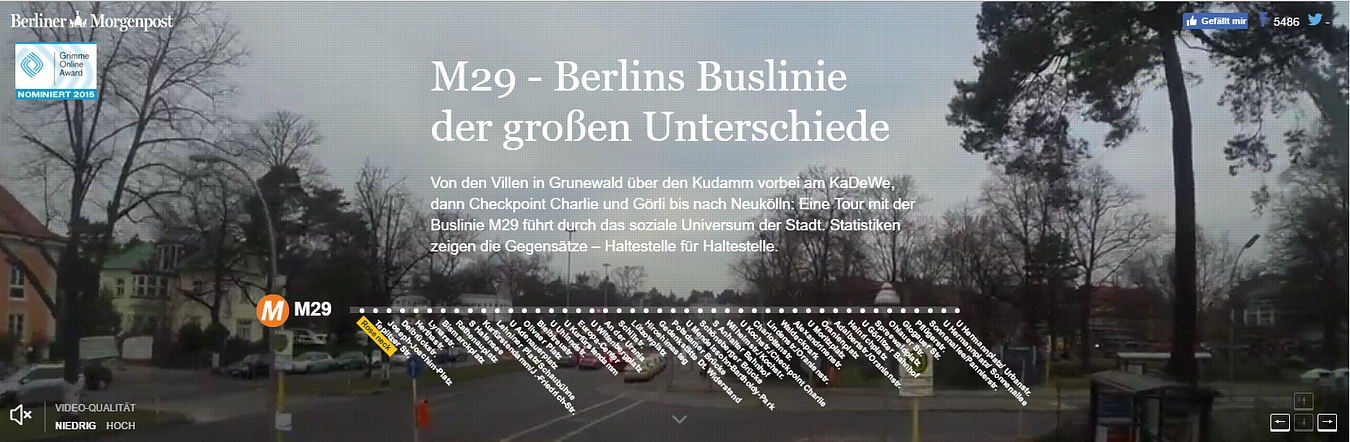

BuzzFeed’s ‘Hidden Spy Planes’

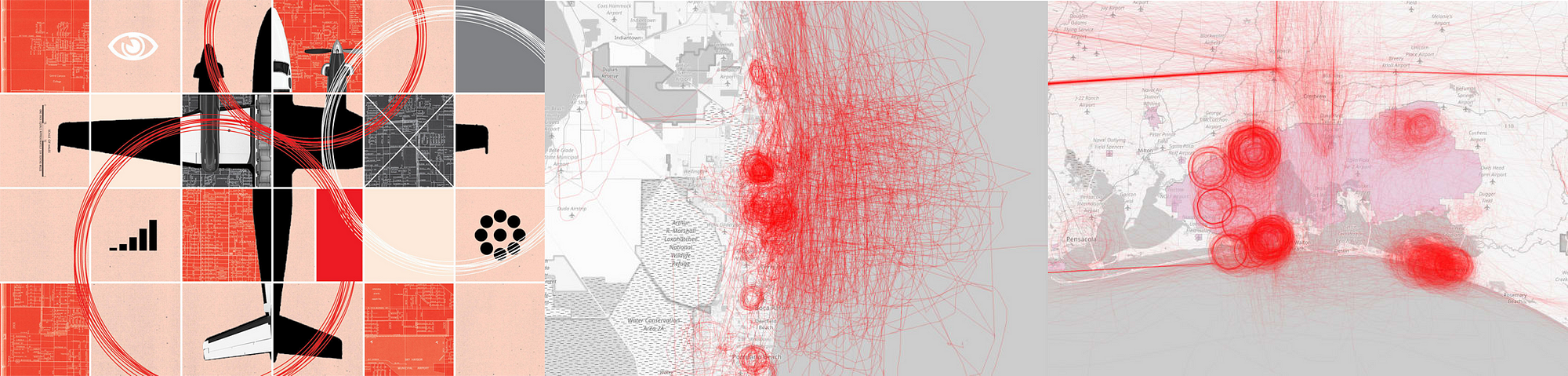

Peter Aldhous is the brain behind BuzzFeed News’s machine learning project ‘Hidden Spy Planes’. The investigation revealed how US airspace is buzzing with surveillance aircraft operated for law enforcement and the military, from planes tracking drug traffickers to those testing new spying technology. Simon Rogers is data editor for Google (who’s also been contributing to some great work on machine learning, including ProPublica’s Documenting Hate project which provides trustworthy facts on the details and frequency of hate crimes).

We asked both of them to sit down for a chat on the Data Journalism Awards Slack team.

What is it about AI that gets journalists so interested? How can it be used in data journalism?

Peter Aldhous: I think the term AI is used way too widely, and is mostly used because it sounds very impressive. When you say ‘intelligence’, mostly people think of higher human cognitive functions like holding a conversation, and sci-fi style androids.

But as reporters, we’re often interested in finding the interesting things from a mass of data, text, or images that’s too big to go through manually. That’s something that computers, trained in the right way, can do well.

And I think machine learning is a much more descriptive and less pretentious label for that than AI.

Simon Rogers: There is a big gap between what we’ve been doing and the common perception of self aware machines. I look at it as getting algorithms to do some of the more tedious work.

Why and when should journalists use machine learning?

P.A.: As a reporter, only when it’s the right tool for the job — which likely means not very often. Rachel Shorey of The New York Times was really good on this in our panel on machine learning at the NICAR conference in Chicago in March 2018.

She said things that have solved some problems almost as well as machine learning in a fraction of the time:

– Making a collection of text easily searchable;

– Asking a subject area expert what they actually care about and building a simple filter or keyword alert;

– Using standard statistical sampling techniques.

What kind of ethical/security issues does the use of machine learning in journalism rise?

P.A.: I’m very wary of using machine learning for predictions of future events. I think data journalism got its fingers burned in the 2016 election, failing to stress the uncertainty around the predictions being made.

There’s maybe also a danger that we get dazzled by machine learning, and want to use it because it seems cool, and forget our role as watchdogs reporting on how companies and government agencies are using these tools.

I see much more need for reporting on algorithmic accountability than for reporters using machine learning themselves (although being able to do something makes it easier to understand, and possible to reverse engineer.)

If you can’t explain how your algorithm works to an editor or to your audience, then I think there’s a fundamental problem with transparency.

I’m also wary of the black box aspect of some machine learning approaches, especially neural nets. If you can’t explain how your algorithm works to an editor or to your audience, then I think there’s a fundamental problem with transparency.

S.R.: I agree with this — we’re playing in quite an interesting minefield at the moment. It has lots of attractions but we are only really scratching the surface of what’s possible.

But I do think the ethics of what we’re doing at this level are different to, say, developing a machine that can make a phone call to someone.

‘This Shadowy Company Is Flying Spy Planes Over US Cities’ by BuzzFeed News

What tools out there you would recommend in order to run a machine learning project?

P.A.: I work in R. Also good libraries in Python, if that’s your religion. But the more difficult part was processing the data, thinking about how to process the data to give the algorithm more to work with. This was key for my planes project. I calculated variables including turning rates, area of bounding box around flights, and then worked with the distribution of these for each planes, broken into bins. So I actually had 8 ‘steer’ variables.

This ‘feature engineering’ is often the difference between something that works, and something that fails, according to real experts (I don’t claim to be one of those). More explanation of what I did can be found on Github.

There is simply no reliable national data on hate crimes in the US. So ProPublica created the Documenting Hate project.

S.R.: This is the big change in AI — the way it has become so much easier to use. So, Google hat on, we have some tools. And you can get journalist credits for them.

This is what we used for the Documenting Hate project:

It also supports a tonne of languages:

With Documenting Hate, we were concerned about having too much confidence in machine learning ie restricting what we were looking for to make sure it was correct.

ProPublica’s Scott Klein referred to it as an ‘over eager student’, selecting things that weren’t right. That’s why our focus is on locations and names. Even though we could potentially widen that out significantly

P.A.: I don’t think I would ever want to rely on machine learning for reporting. To my mind, its classifications need to be ground-truthed. I saw the random forest model used in the ‘Hidden Spy Planes’ story as a quick screen for interesting planes, which then required extensive reporting with public records and interviews.

What advice do you have for people who’d like to use machine learning in their upcoming data journalism projects?

P.A.: Make sure that it is the right tool for the job. Put time into the feature engineering, and consult with experts.

You may or may not need subject matter expert; at this point, I probably know more about spy planes than most people who will talk about them, so I didn’t need that. I meant an expert in processing data to give an algorithm more to work with.

Don’t do machine learning because it seems cool.

Use an algorithm that you understand, and that you can explain to your editors and audience.

Right tool for the job? Much of the time, it isn’t.

Don’t do this because it seems cool. Chase Davis was really good in the NICAR 2018 panel on when machine learning is the right tool:

- Is our task repetitive and boring?

- Could an intern do it?

- If you actually asked an intern to do it, would you feel an overwhelming sense of guilt and shame?

- If so, you might have a classification problem. And many hard problems in data journalism are classification problems in disguise.

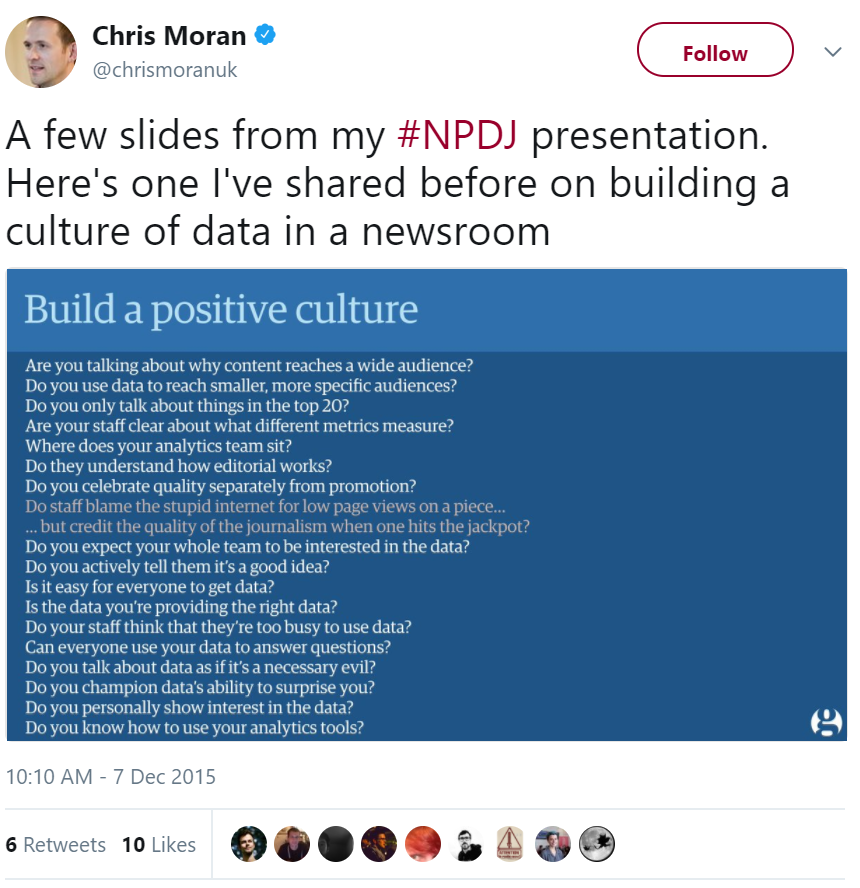

We need to do algorithmic accountability reporting on ourselves! Propublica has been great on this:

But as we use the same techniques, we need to hold ourselves to account

S.R.: Yep — this is the thing that could become the biggest issue in working with machine learning.

What would you say is the biggest challenge when working on a machine learning project: the building of the algorithm, or the checking of the results to make sure it’s correct, the reporting around it or something else?

P.A.: Definitely not building the algorithm. But all of the other stuff, plus feature engineering.

S.R.: We made a list:

- We wanted to be sure, so we cut stuff out.

- We still need to manually delete things that don’t fit.

- Critical when thinking about projects like this — the map is not the territory! Easy to conflate amount of coverage with amount of hate crimes. Be careful.

- Always important to have stop words. Entity extractors are like overeager A students and grab things like ‘person: Man’ and ‘thing: Hate Crime’ which might be true but aren’t useful for readers.

- Positive thing: it isn’t just examples of hate crimes it also pulls in news about groups that combat hate crimes and support vandalized mosques, etc.

It’s just a start: more potential around say, types of crimes.

I fear we may see media companies use it as a tool to cut costs by replacing reporters with computers that will do some, but not all, of what a good reporter can do, and to further enforce the filter bubbles in which consumers of news find themselves.

Hopes & wishes for the future of machine learning in news?

P.A.: I hope we’re going to see great examples of algorithmic accountability reporting, working out how big tech and government are using AI to influence us by reverse engineering what they’re doing.

Julia Angwin and Jeff Larson’s new startup will be one to watch on this:

I fear we may see media companies use it as a tool to cut costs by replacing reporters with computers that will do some, but not all, of what a good reporter can do, and to further enforce the filter bubbles in which consumers of news find themselves.

Here’s a provocative article on subject matter experts versus dumb algorithms:

Peter Aldhous tells us the story behind his project ‘Hidden Spy Planes’:

‘Back in 2016 we published a story documenting four months of flights by surveillance planes operated by FBI and Dept of Homeland Security.

I wondered what else was out there, looking down on us. And I realised that I could use aspects of flight patterns to train an algorithm on the known FBI and DHS planes to look for others. It found a lot of interesting stuff, a grab bag of which mentioned in this story.

But also, US Marshals hunting drug cartel kingpins in Mexico, and a military contractor flying an NSA-built cell phone tracker.’

Should all this data be made public?

Interestingly, the military were pretty responsive to us, and made no arguments that we should not publish. Certain parts of the Department of Justice were less pleased. But the information I used was all in the public, and could have been masked from flight the main flight tracking sites. (Actually DEA does this.)

US Marshals operations in Mexico are very controversial. We strongly feel that highlighting this was in the public interest.

About the random forest model used in BuzzFeed’s project:

Random forest is basically a consensus of decision tree statistical classifiers. The data journalism team was me, all of the software was free and open source. So it was just my time.

The machine learning part is trivial. Just a few lines of code.

If you had had a team to help with this, what kinds of people would you have included?

Get someone with experience to advise. I had excellent advice from an academic data scientist who preferred not to be acknowledged. I did all the analysis, but his insights into how to go about feature engineering were crucial.

Marianne Bouchart is the founder and director of HEI-DA, a nonprofit organisation promoting news innovation, the future of data journalism and open data. She runs data journalism programmes in various regions around the world as well as HEI-DA’s Sensor Journalism Toolkit project and manages the Data Journalism Awards competition.

Before launching HEI-DA, Marianne spent 10 years in London where she worked as a web producer, data journalism and graphics editor for Bloomberg News, amongst others. She created the Data Journalism Blog in 2011 and gives lectures at journalism schools, in the UK and in France.