This article was originally published on the Data Journalism Awards Medium Publication managed by the Global Editors Network. You can find the original version right here.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Lessons learned from an online discussion with experts

The COP23 conference is right round the corner (do I hear “climate change”?) and many data journalists around the world may wonder: How do you go about reporting on environmental data?

With the recent onslaught of hurricanes, such as Harvey, Irma, and Maria, and wildfires in Spain, Portugal and California, data journalists have been working hard to interpret scientific data, as well as getting creative to make it reader friendly.

The COP23 (do I hear climate change?) also serves as a great opportunity for data journalists to take a step back and ask:

What is the best way of reporting on data related to the environment? Where do you find the data in the first place? How do you make it relatable to the public and which challenges do you face along the way?

From top left to bottom right: Kate Marvel of NASA GISS (USA), James Anderson of Global Forest Watch (USA), Rina Tsubaki of European Forest Institute (Spain), Gustavo Faleiros of InfoAmazonia (Brazil), Elisabetta Tola of Formicablu (Italy), and Tim Meko of The Washington Post (USA)

We gathered seven amazing experts on the Data Journalism Awards Slack team on 5 October 2017 to tackle these questions. Tim Meko of The Washington Post (USA), Gustavo Faleiros of InfoAmazonia (Brazil), Rina Tsubaki of European Forest Institute (Spain), Kate Marvel of NASA GISS (USA), Elisabetta Tola of Formicablu (Italy), Octavia Payne and James Anderson of Global Forest Watch (USA), all took part in the discussion.

Here is a recap of what we’ve learned including tips and useful links.

Environmental data comes in many formats…only known by scientists

When it comes to working with environmental data, both journalists and scientists seem to be facing challenges. The main issue seems not to come from scarcity of data but rather from what journalists can do with it, as Elisabetta Tola of Formicablu (Italy) explained:

‘Things are still quite complicated because we have more data available than before but it is often difficult to interpret and to use with journalistic tools’, she said.

There also seems to be a gap between the speed at which data formats evolve in that area and how fast journalists learn how to work with these formats.

‘I think we are still in a moment where we know just a little about data formats. We know about spreadsheets and geodata, but then there are all these other formats, used only by scientists. And I am not really sure how we could use those’, said Gustavo Faleiros of InfoAmazonia (Brazil).

Environmental data should be more accessible and easy to interpret and scientists and journalists should be encouraged to work hand-in-hand more often. The existing incentive structure makes that hard: ‘Scientists don’t get paid or promoted for talking to journalists, let alone helping process data’, said Kate Marvel of NASA GISS (USA).

So what could be done to make things better?

“We need to open up more channels between journalists and scientists: find more effective ways of communicating’, said Elisabetta Tola of Formicablu.

We also need more collaboration not just among data journalism folks, but with larger communities.

‘Really, it is a question of rebuilding trust in media and journalism’, said Rina Tsubaki of European Forest Institute.

‘I think personalising stories, making them hyper-local and relevant, and keeping the whole process very transparent and open are key’, said James Anderson of Global Forest Watch.

Indeed, there seems to be a need to go further than just showing the data: ‘People feel powerless when presented with giant complex environmental or health problems. It would be great if reporting could go one step further and start to indicate ‘what’s the call to action’. That may involve protecting themselves, engaging government, responding to businesses’, said James Anderson of Global Forest Watch.

Top idea raised during the discussion: “It would be great to have something like Hacks&Hackers where scientists and journalists could work together. Building trust between these communities would improve the quality of environmental reporting but also the reward, at least in terms of public recognition, of scientists work.” Suggested by Elisabetta Tola of Formicablu.

To make environmental data more ‘relatable’, add a human angle to your story

As the use of environmental data has become much more mainstream, at least in American media markets, audiences can interact more directly with the data than ever before.

‘But we will have to find ways to keep innovating, to keep people’s attention, possibly with much more personalised data stories (what does the data say about your city, your life in particular, for example)’, said James Anderson of Global Forest Watch.

‘Characters! People respond to narratives, not data. Even abstract climate change concepts can be made engaging if they’re embedded in a story’, said Kate Marvel of NASA GISS.

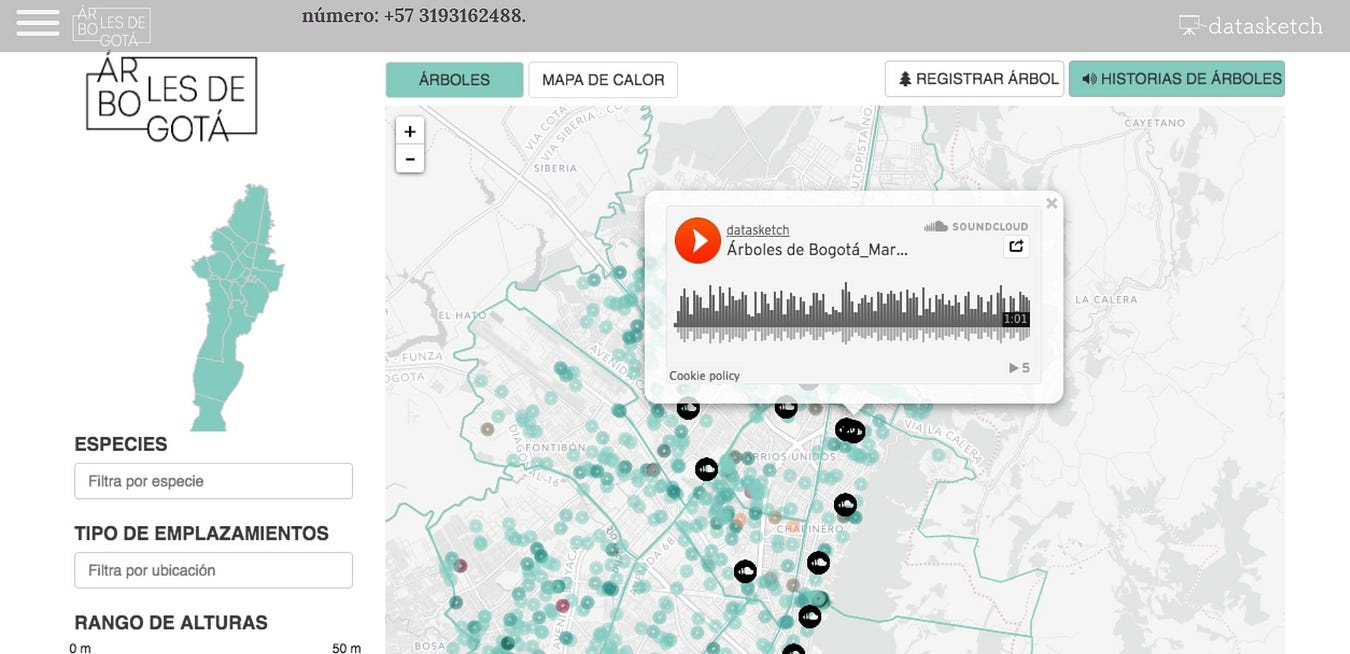

For example, this project by Datasketch, shows how Bogotá has changed radically in the last 30 years. ‘One of the main transformations’, the website says ‘is in the forestation of the city as many of the trees with which the citizens grew have disappeared’.

This project by Datasketch, shows how Bogotá has changed radically in the last 30 years and include citizen’s stories of trees

With this project, Juan Pablo Marín and his team attached citizen stories to specific trees in their city. They mapped 1.2 million trees and enabled users to explore narrated stories by other citizens on a web app.

‘I like any citizen science efforts, because that gets a community of passionate people involved in actually collecting the data. They have a stake in it’, James Anderson of Global Forest Watch argued.

He pointed out to this citizen science project where scientists are tracking forest pests through people’s social media posts.

One more idea for engaging storytelling on climate change: Using art to create a beautiful and visual interactive:

Illustrated Graphs: Using Art to Enliven Scientific Data by Science Friday

Shared by Rina Tsubaki of European Forest Institute

Tips on how to deal with climate change sceptics

‘Climate denial isn’t about science — we can’t just assume that more information will change minds’, said Kate Marvel of NASA GISS.

Most experts seem to agree. ‘It often is more of a tribal or cultural reaction, so more information might not stick. I personally think using language other than ‘climate change’, but keeping the message (and call to action to regulate emissions) can work’, said James Anderson of Global Forest Watch.

A great article about that, by Hiroko Tabuchi, and published by The New York Times earlier this year can be found here: In America’s Heartland, Discussing Climate Change Without Saying ‘Climate Change’

‘Keeping a high quality and a very transparent process can help people who look for information with an open mind or at least a critical attitude’, Elisabetta Tola of Formicablu added.

A great initiative where scientists are verifying media’s accuracy:

Climate Feedback

Shared by Rina Tsubaki of European Forest Institute

Places to find data on the environment

The Planet OS Datahub makes it easy to build data-driven applications and analyses by providing consistent, programmatic access to high-quality datasets from the world’s leading providers.

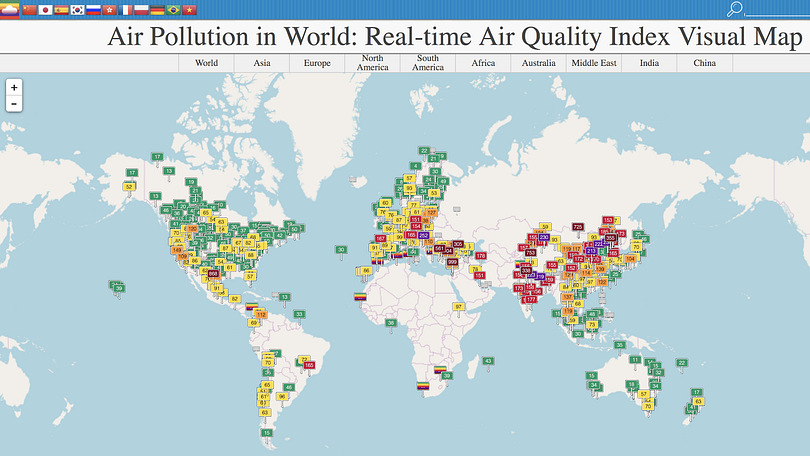

AQICN looks at air pollution in the world with a real-time air quality index.

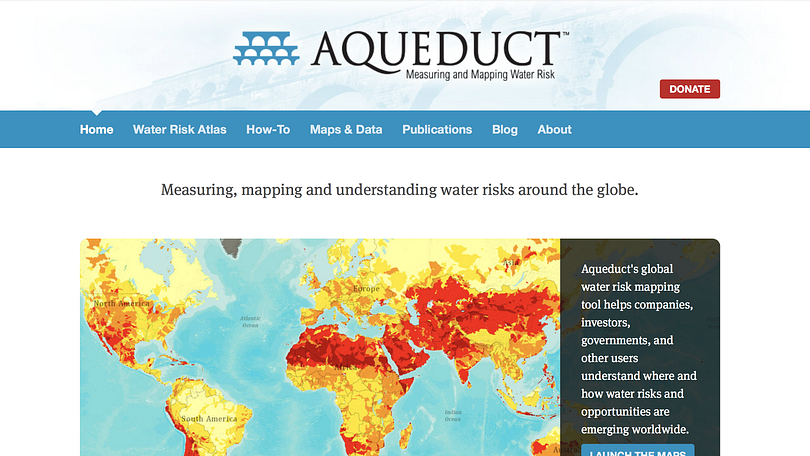

Aqueduct by the World Resources Institute, for mapping water risk and floods around the world.

The Earth Observing System Data and Information System (EOSDIS) by NASA provides data from various sources — satellites, aircraft, field measurements, and various other programs.

FAOSTAT provides free access to food and agriculture data for over 245 countries and territories and covers all FAO regional groupings from 1961 to the most recent year available.

Global Forest Watch offers the latest data, technology and tools that empower people everywhere to better protect forests.

The Global Land Cover Facility (GLCF) provides earth science data and products to help everyone to better understand global environmental systems. In particular, the GLCF develops and distributes remotely sensed satellite data and products that explain land cover from the local to global scales.

Google Earth Engine’s timelapse tool is useful for satellite imagery, enables you to map changes over time.

Planet Labs is also great for local imagery and monitoring. Their website feature practical examples of where their maps and satellite images were used by news organisations.

News from our community: In a few months, James Anderson and the team at Global Forest Watch will launch an initiative called Resource Watch which will work as an aggregator and tackle a broader set of environmental issues.

“It was inspired by the idea that environmental issues intersect — for example forests affect water supply, and fires affect air quality. We wanted people to be able to see how interconnected these things are,” said Anderson.

What to do if there is no reliable data: the case of non-transparent government

It is not always easy or straightforward to get data on the environment, and the example of Nigeria was brought about during our discussion by a member of the DJA Slack team.

‘This is because of hypocrisy in governance’, a member argued.

‘I wish to say that press freedom is guaranteed in Nigeria on paper but not in reality.

You find that those in charge of information or data management are the first line of gatekeepers that will make it practically impossible for journalists to access such data.

I can tell you that, in Nigeria, there is no accurate data on forestry, population figure and so on’.

So what is the way out? Here are some tips from our experts:

‘I would try using some external, no official sources. You can try satellite imagery by NASA or Planet Labs or even Google, then distribute via Google Earth or their Google News Lab. Also you can download deforestation, forest fires and other datasets from sites of University of Maryland or the CGIAR Terra-i initiative’, Gustavo Faleiros of InfoAmazonia suggested.

Here is an example:

Nigeria DMSP Visible Data By NOAA/NGDC Earth Observation Group

‘I think with non-transparent governments, it is sometimes useful to play both an “inside game” (work with the government to slowly [publish] more and more data under their own banner) and an “outside game” (start providing competing data that is better, and it will raise the bar for what people [should] expect)’, said James Anderson of Global Forest Watch.

‘It’s a really tough question. We’ve worked with six countries in the Congo Basin to have them improve their data collection, quality-control, and sharing. They now have key land data in a publicly-available portal. But it took two decades of hard work to build that partnership’, he added.

‘I think this is exactly the case when a good connection with local scientists can help’, said Elisabetta Tola of Formicablu. ‘There are often passionate scientists who really wish to see their data out. Especially if they feel it could be of use to the community. I started working on data about seismic safety over five years ago. I am still struggling to get the data that is hidden in tons of drawers and offices. I know it’s there’, she added.

‘For non-transparent governments, connect with people who are behind facilitating negotiations for programmes like REDD to get insider view’, added Rina Tsubaki of European Forest Institute.

CARTO is the platform for turning location data into business outcomes.

What tools do you use when reporting on environmental data?

Here is what our data journalism community said they played with on a regular basis:

CARTO enriches your location data with versatile, relevant datasets, such as demographics and census, and advanced algorithms, all drawn from CARTO’s own Data Observatory and offered as Data as a Service.

QGIS is a free and open source geographic information system. It enables you to create, edit, visualise, analyse and publish geospatial information.

OpenStreetMap is a map of the world, created by members of the public and free to use under an open licence.

Google Earth Pro and Google Earth Engine help you create maps with advanced tools on PC, Mac, or Linux.

Datawrapper, an open source tool helping everyone to create simple, correct and embeddable charts in minutes.

R, Shiny and Leaflet with plugins were used to make these heatmaps of distribution of tree species in Bogotá.

D3js, a JavaScript library for visualizing data with HTML, SVG, and CSS.

Flourish makes it easy to turn your spreadsheets into world-class responsive visualisations, maps, interactives and presentations. It is also free for journalists.

Great examples of data journalism about the environment we’ve come across lately

How Much Warmer Was Your City in 2015?

By K.K. Rebecca Lai for The New York Times

Interactive chart showing high and low temperatures and precipitation for 3,116 cities around the world.

(shared by Gustavo Faleiros of InfoAmazonia)

What temperature in Bengaluru tells about global warming

By Shree DN for Citizen Matters

Temperature in Bengaluru was the highest ever in 2015. And February was the hottest. Do we need more proof of global warming?

(shared by Shree DN of Citizen Matters in India)

Data Science and Climate Change: An Audience Visualization

By Hannah Chapple for Affinio Blog

Climate change has already been a huge scientific and political topic in 2017. In 2016, one major win for climate change supporters was the ratifying of the Paris Agreement, an international landmark agreement to limit global warming.

(shared by Rina Tsubaki of European Forest Institute)

Google’s Street View cars can collect air pollution data, too

By Maria Gallucci for Mashable

“On the question of compelling environmental stories to prioritize, (this was a bit earlier in the thread) I feel like hyper-local air quality (what is happening on your street?) is powerful stuff. People care about what their family breathes in, and its an urgent health crisis. Google StreetView cars are now mapping this type of pollution in some places.”

(shared by James Anderson of Global Forest Watch)

This Is How Climate Change Will Shift the World’s Cities

By Brian Kahn for Climate Central

Billions of people call cities home, and those cities are going to get a lot hotter because of climate change.

(shared by Rina Tsubaki of European Forest Institute)

Treepedia :: MIT Senseable City Lab

Exploring the Green Canopy in cities around the world

(shared by Rina Tsubaki of European Forest Institute)

Losing Ground

By ProPublica and The Lens

Scientists say one of the greatest environmental and economic disasters in the nation’s history — the rapid land loss occurring in the Mississippi Delta — is rushing toward a catastrophic conclusion. ProPublica and The Lens explore why it’s happening and what we’ll all lose if nothing is done to stop it.

(shared by Elisabetta Tola of Formicablu)

Watergrabbing

A Story of Water, looks into the water-hoarding phenomenon. Every story explains a specific theme (transboundary waters, dams, hoarding for political and economic purposes), and shows the players involved, country-by-country. Take time to read and discover what water grabbing means. So that water can become a right for each country and every person.

(shared by Elisabetta Tola of Formicablu)

Ice and sky

By Wild-Touch

Discover the history and learn about climate changes — the interactive documentary

(shared by Gustavo Faleiros of InfoAmazonia)

Extreme Weather

By Vischange.org

The resources in this toolkit will allow communicators to effectively communicate extreme weather using strategically framed visuals and narratives. Watch the video to see it in action!

(shared by Rina Tsubaki of European Forest Institute)

Plus, there is a new version of Bear 71 available for all browsers:

Bear 71 VR

Explore the intersection of humans, nature and technology in the interactive documentary. Questioning how we see the world through the lens of technology, this story blurs the lines between the wild world, and the wired one.

(shared by Gustavo Faleiros of InfoAmazonia)

To see the full discussion, check out previous ones and take part in future ones, join the Data Journalism Awards community on Slack!

Marianne Bouchart is the founder and director of HEI-DA, a nonprofit organisation promoting news innovation, the future of data journalism and open data. She runs data journalism programmes in various regions around the world as well as HEI-DA’s Sensor Journalism Toolkit project and manages the Data Journalism Awards competition.

Before launching HEI-DA, Marianne spent 10 years in London where she worked as a web producer, data journalism and graphics editor for Bloomberg News, amongst others. She created the Data Journalism Blog in 2011 and gives lectures at journalism schools, in the UK and in France.