Looking back on some tumultuous years in journalism, including Donald Trump’s campaign against fake news and the rise of the digital area, we asked Jimmy Wales, founder of Wikipedia and WikiTribune, five quick questions about his view on the current state of trust in journalism.

We interviewed Jimmy Wales at the GEN Summit 2018 in Lisbon where he did a session on trust with Matt Kelly (Archant Group) and Ed Williams (Edelman UK) © Rainer Mirau for GEN

How would you describe the state of trust in journalism?

Journalism has been under huge financial pressure for a few years and somehow lost its way. However, trust is now starting to get back after the public realized that quality journalism matters.

Access to Wikipedia is free. Does that mean that trust is free?

Trust is about honesty and this does not really cost anything. The other way round, money can corrupt honesty.

How do you go about Fake News?

We have to manage them with trust. In the mainstream and quality media we’ve got to do all things right and share transcripts, audios, … things to prove what we are saying. Only this way we can restore trust and show the people that we are not simply making something up.

How do you verify data for Wikipedia?

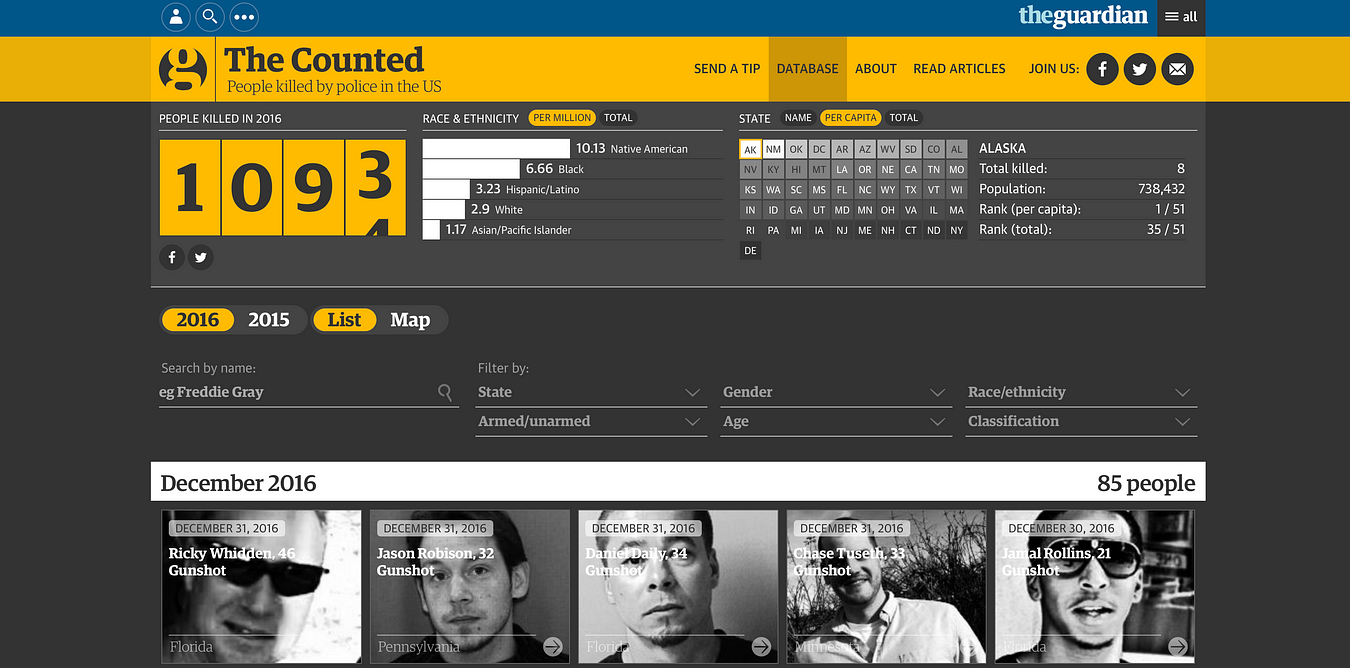

We verify the data with very old-fashioned techniques, like transcripts, interviews and documents. All of this is very old-fashioned journalism. If you look at later techniques, data journalism, for instance, is a very important tool in journalism of the modern world. So much can be learned from large sets of data, particularly financial contributions to politicians. It is a rich source of very good information.

How do you see the future of journalism?

I am optimistic about journalism in the future because it is a core function in society. And even if the transition from digital business models has been very difficult, I do not think that the public does not care about the truth anymore. They do. We just have to find models to make it work!

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Michaela Gruber is a journalism and media management student, based in Vienna, Austria. During her studies she spent a semester abroad in France, where she started working for HEI-DA.

Michaela Gruber is a journalism and media management student, based in Vienna, Austria. During her studies she spent a semester abroad in France, where she started working for HEI-DA.

As the company’s communication officer, she is in charge of the Data Journalism Blog and several social media activities. This year, Michaela was HEI-DA’s editor covering the Data Journalism Awards in Lisbon, Portugal.